Introduction

COP29¹ will be held in Baku, Azerbaijan from November 11 to 22 between two other key international environmental conferences: COP16² for biodiversity in Cali, Colombia (Oct 21, 2024 – Nov 1, 2024) and COP16³ for desertification and soil degradation in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia (Dec 2, 2024 – Dec 13, 2024). This convergence of conferences allows world leaders to converge their efforts on three interconnected topics, climate change, biodiversity loss and land degradation, at a time when extreme climate events keep occurring. The record-breaking rainfall and deadly flash floods that hit Valencia, Spain in late October 2024 is one of the latest such events that are bound to become more likely and more severe due to anthropogenic climate change.

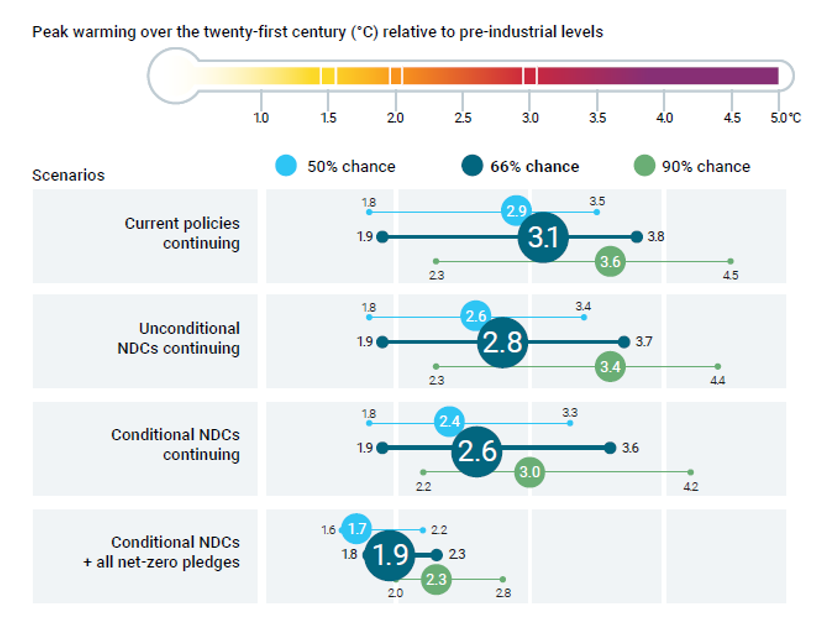

COP29 in Baku also comes after the release of the 2024 UNEP Emissions Gap Report⁴ – which states that implementing current policies would deliver up to 3.1°C of warming while implementing both conditional⁵ and unconditional5 NDCs (Nationally Determined Contribution) would lead to 2.6°C of warming. These levels of global warming would have catastrophic effects and necessitate costly adaptation measures and investments. However, the report also highlights that it remains technically possible to cut emissions in line with a 1.5°C pathway and that a large share of the efforts should come from G20 members which alone accounted for 77% of emissions in 2023.

- Like every year, COP29 agenda is very busy. The major issues to be addressed in the Baku negotiations are as follows:

- Financing climate action, and above all setting a new collective quantified goal (NCQG) for the post-2025 period,

- Finalization of the rules for implementing Article 6 (market-based and non-market-based mechanisms) almost 10 years after the adoption of the Paris Agreement,

- Operationalization of the loss and damage fund, abbreviated L&D Fund hereafter,

- Global target on adaptation through the NAPs – National Adaptation Plans

- Mitigation ambition in the context of the upcoming submission of updated or new NDCs (official deadline: February 10, 2025),

- Concrete implementation of the results of the Global Stocktake, and in particular the objective of ensuring a fair, orderly and equitable transition away from fossil fuels in energy systems (paragraph 28(e) of decision 1/CMA-5).

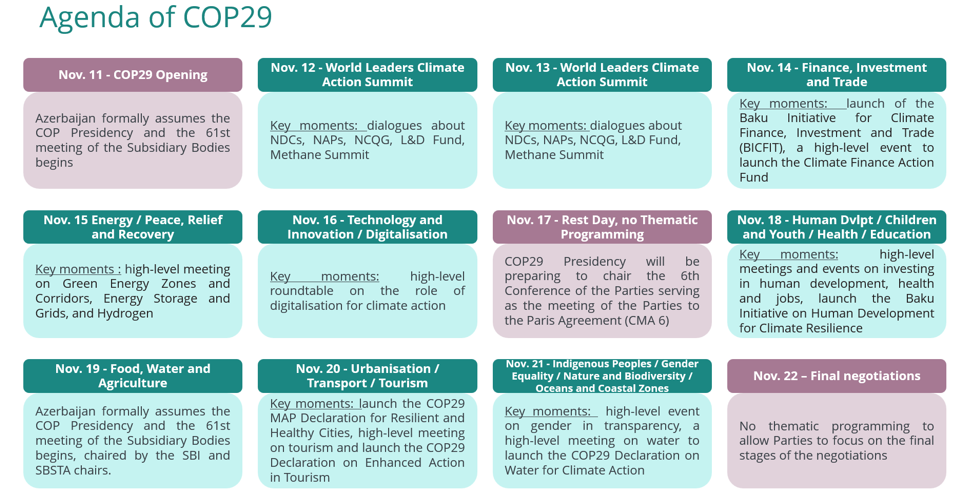

These issues will be addressed throughout two weeks with the agenda presented in Figure 1 below. Thematic days at COP29 will cover a range of critical topics, each providing a dedicated platform for in-depth discussions, side events, and negotiations.

Figure 1 – Items of the COP29 Meetings Agenda

(I Care, adapted from COP 29 Presidential Action Agenda – Global Initiatives)

In the following article, we’ll focus on three essential topics that will be tackled during this 29th COP by taking stock of the situation and outlining expectations and potential solutions.

Focus 1 – Boosting NDCs

Situation of as November 2024

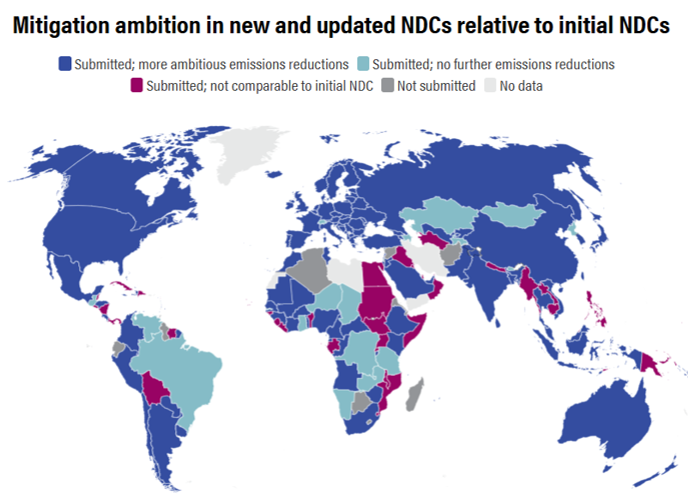

The first NDCs were part of the Paris Agreement agreed by all 196 Parties. The first update was in 2020, and these commitments should be updated again in February 2025. The target is to achieve them by 2035. These pledges represent the global collective efforts to tackle climate change under the Paris Agreement. Several major emitters have indicated that they will announce or release their new climate commitments by this year’s COP, including Brazil (the host of next year’s UN climate summit), the United Kingdom and the United Arab Emirates. Figure 2 below offers a comprehensive view of the current state of global NDCs (last updated in January 2024).

Figure 2 – Mitigation ambition in new and updated NDCs relative to initial NDCs – last updated in January 2024

(Source: World Resources Institute and Climate Watch – https://www.wri.org/ndcs/tracking-progress)

Current policies put us on track to limit global warming to a maximum of 3.1°C over the course of the century while the implementation of unconditional or conditional NDC scenarios lowers these projections to 2.8°C and 2.6°C, respectively (see Figure 3 below for estimated ranges). Under these three scenarios, the average global warming values indicate that the chance of limiting global warming to 1.5°C is zero. The only scenario that gets closer to the temperature goal of the Paris Agreement is the most optimistic, called “Conditional NDCs + all net-zero pledges”, which assumes that countries achieve their objectives at both short and long-term and receive sufficient financing when necessary to implement measures to facilitate their emissions reduction trajectories.

Figure 3 – Projections of global warming under the pledge-based scenarios assessed

(Source: UNEP 2024 Emissions Gap Report)

Expected outcomes of the negotiations

During COP29, negotiations will focus on the importance for countries to align their NDCs with a 1.5°C pathway for 2030 and 2035 to revive the possibility of limiting global warming to 1.5°C. To do so, countries must include all gases listed in the Kyoto Protocol, cover all sectors, set specific and quantitative targets in relation to a base year and detail conditional and unconditional elements. It will also be expected from countries to be transparent about how the NDC submission reflects both a fair share and the highest possible ambition given their historical emissions and economic situation. Targets determined by the NDCs will require additional investments to make possible tripling the renewable energy capacity by 2030 compared with 2023 levels, doubling the global average annual rate of energy efficiency improvements by 2030 compared with 2023 levels, transitioning away from fossil fuels in energy systems, and conserving, protecting and restoring nature and ecosystems.

These objectives and ways of improving current NDCs are well-known by now and discussions will also focus on how developed countries can provide technical assistance and technology transfer to support developing countries in the implementation of their own NDCs. This second step is crucial for the operationalization part of NDCs. Technical assistance can be done by connecting countries’ representatives with experts and resources and providing training programs to share knowledge and build capacity. Technology transfer involves sharing both non-mature and mature low-carbon technologies and associated skills or helping developed countries obtain licenses to use patented technologies to support the deployment of climate action.

With clear targets countries will signal the direction of travel to investors, including in the private sector, to help direct more finance toward climate action.

Focus 2 – Accelerating climate action financing

Situation of as November 2024

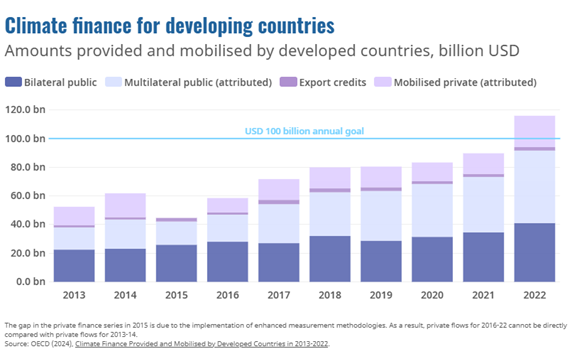

In 2009, developed countries agreed they would collectively mobilize $100 billion annually by 2020 to support developing countries’ climate mitigation and adaptation strategies. According to the OECD, this goal was met for the first time with a two-year delay in 2022 (see Figure 4 below). Then, in 2015 during the Paris Agreement, countries decided to set a “new collective quantified goal on climate finance” (NCQG) to replace the existing goal of $100 billion per year as the initial amount was known to be insufficient. The NCQG is meant to be adopted this year at COP29 in Azerbaijan. This more ambitious goal is essential to helping vulnerable countries adopt clean energy and other low-carbon solutions. Many developing countries with conditional NDCs cannot strengthen, or even fulfil, their climate pledges without it.

Figure 4 – Amounts provided by developed countries to finance climate action for developing countries

(Source OECD – https://www.oecd.org/en/topics/sub-issues/climate-finance-and-the-usd-100-billion-goal.html)

Expected outcomes of the negotiations

Defining an effective NCQG relies on several issues, some of which are discussed hereafter:

A. Finding the right amount of money

B. Identifying which countries should contribute

C. Choosing a timeframe

D. Ensuring transparency in the processes

A. The initial value of $100 billion per year was a political agreement rather than science-based. Current scientific reports give different intervals but the Independent High-Level Expert Group on Climate Finance (IHLEG) said US$2.4 trillion of investment a year would be necessary by 2030 (in emerging markets and developing countries (outside China) across the priorities of a just energy transition, adaptation and resilience, loss and damage, and the conservation and restoration of nature. This amount represents a substantive increase but appears manageable in the broader context of the US$110 trillion value which is generated every year by the global economy and financial markets.

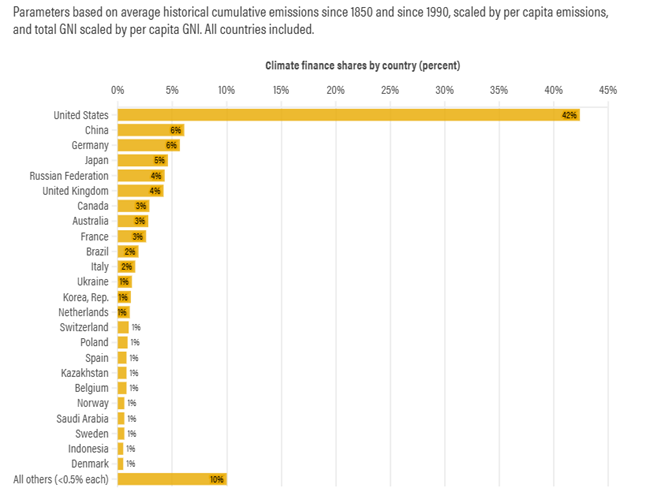

B. Article 9 of the Paris Agreement recognizes that developed countries – defined in this case as the 24 countries that were OECD members in 1992 when the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) was signed – are primarily responsible for providing climate finance to developing nations. However, developed countries argue that the global economy has drastically changed in the last decades and that more countries could contribute today. Figure 5 below illustrates a potential distribution of financing from different countries under various parameters. The recent US presidential election results add another layer of uncertainty to the position the United States will adopt on its climate ambitions and in future political negotiations.

C. The timeframe at which countries are expected to achieve the objective is also under debate. End dates vary between 5 years to 20 years. Near-term end dates could be difficult to achieve because of the lack of stability and predictability for countries, However, long-term end dates delay accountability from countries and make it harder to take into account inflation, shifting costs of technology or future climate impacts. An intermediate solution would be to agree on mid to long-term targets with revisions every five years.

D. When the initial goal of $100 billion per year was agreed in 2009, there was no official mechanism to hold developed countries accountable for achieving it. At COP26 in Glasgow 2021, the UNFCCC’s Standing Committee on Finance (SCF) was tasked with assessing progress towards the $100 billion goal. The new climate finance goal is likely to incorporate such tracking mechanisms to improve its efficiency. Some stakeholders suggest that existing instruments such as the Enhanced Transparency Framework (ETF)⁶ could be appropriate.

Figure 5 – Illustrative scenario from WRI’s Climate Finance Calculator

(Source WRI – https://www.wri.org/insights/international-climate-finance-which-countries-should-pay)

It is not certain yet that the NCQG will cover loss and damage. Developing countries are advocating in favour of it and recommend creating subgoals for both adaptation and loss and damage to ensure that these areas receive adequate finance.

Focus 3 – Getting forward with the Loss and Damage fund

Situation of as November 2024

Quantifying the extent of current global loss and damage is still very difficult because of the variety of events that can be covered, their different scales of occurrence and their interconnections. Loss and damage range from damage to infrastructures in cities as a result of flooding, to loss of reefs and ecosystems due to sea level rise or even loss of life due to extreme heat. In sum, events that go beyond what people and ecosystems can adapt to. However, it is clear that loss and damage are already occurring on a large scale, and that global warming increases the likelihood of more dramatic events. The latest estimates⁷ by the National Bureau of Economic Research (NBER) indicates that each 1°C of global warming costs the world 12% in gross domestic product (GDP) losses.

In 2024, the Loss and Damage Fund has made significant progress by selecting the Philippines as the host for its board, establishing working relationships with the World Bank, which is in charge of the operationalisation of the fund, and officialising the election of Ibrahima Cheikh Diong as the inaugural Executive Director of the Fund for responding to Loss and Damage, for a four-year term beginning November 1, 2024⁸ . These preliminary steps should be validated during the negotiations and countries should pursue the discussions to improve loss and damage funding arrangements. Negotiators will also review the Warsaw International Mechanism (WIM)⁹, which was established as main vehicle in the UNFCCC process for catalyzing knowledge, action and support for addressing loss and damage.

Expected outcomes of the negotiations

During COP29, expectations will focus on all the progress made on what counts as loss and damage, including extreme weather events and slow onset events. The operationalization of the fund including governance arrangements, implementing a programmatic approach to funding, defining the eligibility criteria for adding money to the fund and benefiting from it, clarifying the links between this fund and other funds or initiatives already developed during previous COPs. Many stakeholders advocate for the fund to be easily accessible and implement clear triggers to ensure quick delivery of support to countries affected by loss and damage. For instance, for fast-onset events, quick access to money is crucial in saving lives and livelihoods and could be set depending on the number of people affected, the expected economic scale of impact (as a percentage of GDP) or other indicators relaying the urgency and scale of the loss and damage impact. For slow-onset events, applying for funding proposals based on several criteria including countries’ own mitigation and adaptation plans could be envisaged.

Conclusion

However, one should hope that they will not overshadow other essential topics such as the agreement to credibly phase out fossil fuel subsidies, a thorny issue that delayed the final phase of negotiations at COP28¹0. As a reminder, COP28 ended on an agreement to “accelerate efforts towards the phase-down of unabated coal power, phase out inefficient fossil fuel subsidies, and other measures that drive the transition away from fossil fuels in energy systems, in a just, orderly and equitable manner” but fossil fuel subsidies in 2022 reached a record high of USD 1.3 trillion¹¹ Donald Trump’s election in November 2024 raises additional concerns as he’s likely to cut spending on green energy and boost US production of fossil fuels. Nonetheless, the clean energy transition saw a rapid boost in the last 4 years in the USA thanks to the Bipartisan Infrastructure Law and the Inflation Reduction Act (IRA) that generated significant investments and created numerous job opportunities. Were measures from the IRA to be curved, both republican and democrats states would have a lot to lose.

Notes and références :

[2] https://www.cop16colombia.com/es/en/

[3] https://www.unccdcop16.org/

[4] https://www.unep.org/resources/emissions-gap-report-2024

[5] When targets are dependent on external financial support, these are marked as “conditional” targets. The targets a country can achieve without external financial support are referred to as “unconditional”.

[6] https://unfccc.int/process-and-meetings/transparency-and-reporting/preparing-for-the-ETF

[7] https://www.nber.org/papers/w32450