An important milestone for biodiversity after the historic COP15

The aim of the 16th Conference of the Parties to the Convention on Biological Diversity, to be held in Cali from 21 October to 1st November 2024, is to implement the 2022 Kunming-Montreal agreement.

With regard to the major announcements and numerous commitments made at COP15[1], COP16 is not likely to represent such an historic agreement but could yet mark an important milestone: after the momentum of 2022, this COP can be considered as a test to see which players and countries will really start to take action.

Having set ambitious targets for international action for nature, parties now need to act. The signatory countries are entering a phase of institutionalising the agreement by submitting their National Biodiversity Strategies and Action Plans (NBSAPs). This COP also intends to make last decisions, take stock of the progress made by countries leading the pack and agree on ways to overcome the obstacles faced by the countries which are least advanced[2].

The slogan chosen for COP16 by host country Colombia has all the makings of a diplomatic sonnet, this time inviting a new player, nature. “Paz con la naturaleza” resonates with initiatives aimed at making natural entities subjects of law. At least, it expresses the wish that diplomats and stakeholders gathered at the COP contribute to reorganising and pacifying the complex relations we have with the natural world.

With biodiversity loss figures that are still worrying and just 6 years to go until the 2030 deadline for “bending the curve”, it is far from certain whether the targets set out at COP 15 will be achieved. While some initiatives targeting climate change have proven successful (i.e. the European Green Deal and, in China the development of renewable energy and electric cars and an ambitious reforestation policy[3]), ambitious policies for biodiversity are still lagging a bit behind. In particular, the agricultural transition is not yet underway, and only 20 countries have unveiled their NBSAPs.

Top agenda items of COP16: drafting NBSAPs, strengthening accountability and closing the nature finance gap

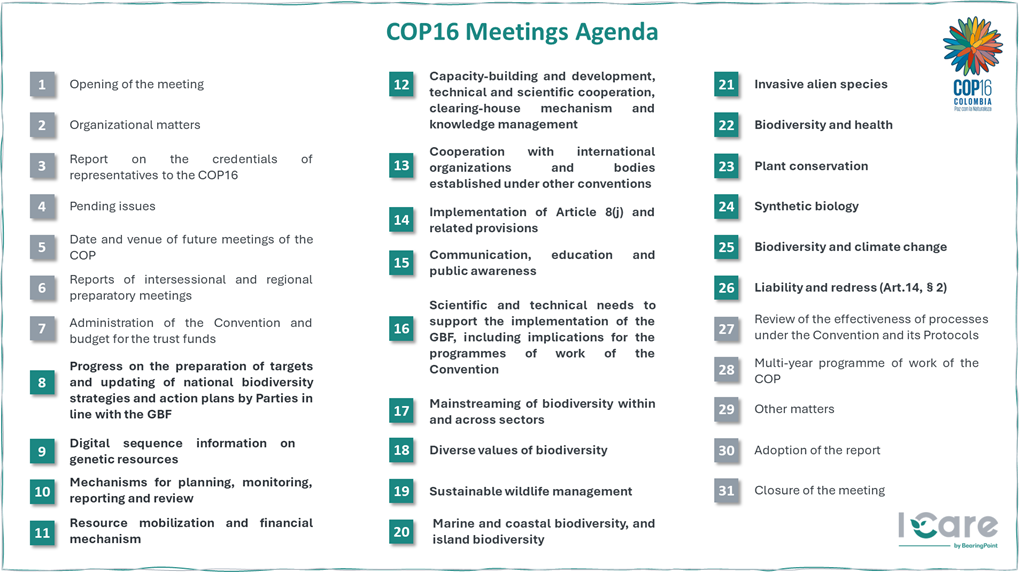

Figure 1 – Items of the COP16 Meetings Agenda (I Care, adapted from: COP16 Meeting documents)

Drafting NBSAPs

NBSAPs are an important component of the operationalisation of the Kunming-Montréal agreement and reviewing progresses made so far by the Parties will be a first agenda point at COP16 (see item 8 in Figure 1). The EU (through its Biodiversity strategy for 2030) as well as different European countries (such as France with its SNB 2030, but also in Ireland, Spain and Hungary) have taken on the challenge and drawn their 2030 biodiversity strategies. COP16 will provide the opportunity to review the extent to which these plans are operational as well as their underlying governance – which is a major topic.

Parties should look at important questions, such as whether NBSAPs have been designed in a participatory way – including the main economic stakeholders as well as representatives from the civil society–, and whether they are supported at the highest decision level, beyond environmental authorities.

Strengthening accountability

Another important item on the agenda will be about accountability[4]: States are making commitments in their NBSAPs and their assessment will be discussed at COP16 (see item 10 of the Agenda) : they will review whether national targets and plans submitted by all countries are in line with the global targets set out by the Global Biodiversity Framework (GBF). This could open a discussion on the need to raise certain ambitions and strengthen strategies, while respecting the sovereignty of each Party.

Closing the nature finance gap

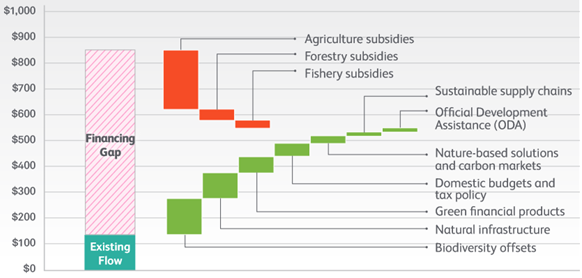

Finally, the question of funding will be brought on the table (see item 11 of the Agenda)[5]. The nature finance gap has been estimated at around 700 billion dollars[6]. Filling this gap is now the subject of objectives 18 (increasing by 200 billion national and international funding) and 19 (redirect 500 billion from harmful subsidies) of the GBF[7].

To close the gap, we need to double official development assistance (from $10 billion to $20 billion per year until 2025, then $30 billion until 2030) as well as national funding (from $78 billion in 2019 to $180 billion per year). In addition, it was decided between COP 15 and COP 16 that a new international fund would be created, under the Global Environment Facility, to ease funding flows between the global North and South. The final scope and operating rules of this new fund will be discussed at COP 16. Besides, the World Bank and the Coalition of Finance Ministers for Climate Action are carrying out studies on innovative mechanisms that could back up or complement this fund: instruments such as biodiversity credits, trust funds for the conservation and sustainable management of forests (CTFs), debt-for-nature swaps, common asset trusts, etc. could prove useful[8].

Figure 2 – Examples of mechanisms to scale up by 2030 to close the biodiversity finance gap (in 2019 US$ billion per year; source : Paulson Institute)

At a side event, the International Advisory Panel on Biodiversity Credits (IAPB) will present high-integrity principles for developing this emerging market mechanism. If such credits are to be useful, IAPB’s framework should avoid the pitfalls of carbon credits. Biodiversity credits should ensure that transfers of funds result in real additional ecological gains on the ground and in the long-term, while guaranteeing affordable prices, equitable stewardship and robust governance[9].

The role of business: supporting governments’ ambitions by making commitments

Business involvement is going to be discussed during the COP (see item 17 of the Agenda) and in dedicated side events, as it is a decisive topic.

Some governments have already incorporated transparency and accountability mechanisms in their national action plans to initiate dialogue with corporates, monitor their progress and help them contribute to a nature-positive society. For example, the European Union (with its Corporate Sustainability Reporting Directive) and China (with its Corporate Sustainability Disclosure Guidelines[10]) have designed regulatory frameworks based on the principle of double materiality.

To complement regulations, voluntary frameworks for economic actors have emerged in recent years. Companies and financial institutions can follow the voluntary reporting framework produced by the Task Force for Nature-related Financial Disclosure (TNFD) to manage their nature-related impacts, dependencies, risks and opportunities, by integrating them into their strategic planning. The Science-Based Target Network (SBTN) initiative is another voluntary framework enabling companies to set science-based targets to reduce their impacts on nature and contribute to a collective effort to restore and regenerate biodiversity, and more generally, to transform their business models into more sustainable ones. I Care is currently experiencing both TNFD and SBTN frameworks with corporates and financial institutions (see TNFD Pilot Test on the Agrifood Sector and our analysis on Science-Based Targets for Nature).

The link between regulations and voluntary frameworks could be discussed during the COP. For instance, bringing together individual scientific targets and internationally and nationally agreed targets could help to align and engage businesses further. This would ensure that efforts are distributed in a way that is acceptable to all sectors and countries. Besides, actions to reach those could be much more easily the subject of public aid or compensation.

Beyond action at individual level, companies can sign joint commitments such as those of Business for Nature. Such collective move showed the maturity of the private sector during COP 15. It encouraged government to set ambitious targets. For COP 16[11], the signatory companies ask to “shift priorities to balance short-term economic gains with long-term environmental health“, and thus that governments should strengthen regulations in favour of ecosystems. This would give companies more visibility to adopt nature-positive strategies with confidence.

Agriculture, a challenge to take one?

The IPBES global assessment (2019) had clearly identified agriculture, fisheries and forestry as the main sources of impact on ecosystems, in terms of both land use and pollution. However, the transition regarding those sectors remains the “elephant in the room” of international negotiations on biodiversity – and so despite all the progresses and initiatives mentioned above. They should draw on international climate discussions, while putting the topic on the table much earlier: indeed, parties involved in climate COP finally managed to discuss the reduction in the use of fossil fuels in 2023 (after 27 COPs!).

Despite the existence of very clear objectives in the Aichi framework (2010-2020), previous NBSAPs had largely ignored these sectors, or had failed to really get them on board. The consensus on tomorrow’s agriculture and a transition path to get there is not broad enough. Harmful subsidies that encourage intensive use, and even over-exploitation of resources, remains a very difficult topic to tackle. The European situation shows it clearly, with the difficult negotiations around the Common Agricultural Policy (CAP) and sometimes violent protests against new environmental public policies[12].

Beyond obstacles, it is key to define the right incentives to guide conventional farming systems transition towards more sustainable ones. To help achieve this goal, various initiatives have been launched to quantify the environmental benefits resulting from agro-ecological practices, such as the Biodiversity Index Assessment Method (BIAM) hosted by OBC, or the Biodiversity Footprinting for the Agricultural Transition (BFAT) project, a multi -stakeholder project led by I Care.

Notes and références :

[1] Replay of our COP15 Biodiversity Webinar is available at this link: Webinaire | L’Accord de la COP15 Biodiversité: quelles implications pour les acteurs privés?

[2] IDDRI. « De la COP 15 à la COP 16, quelles avancées dans la mise en œuvre du cadre mondial pour la biodiversité ? » Paris, France, 2024.

[3] “How is China tackling climate change?” – The London School of Economics and Political Science. Available at: https://www.lse.ac.uk/granthaminstitute/explainers/how-is-china-tackling-climate-change/

[4] Landry, Juliette, Ioannis Agapakis, Matthieu Wemaëre, et Julien Rochette. « For an effective implementation of the post-2020 global biodiversity framework: what is needed at CBD COP15 and beyond ». IDDRI Policy brief 10, no 22 (2022).

[5] Landry, Juliette. « Transforming Multilateral Biodiversity Finance: A Theory of Change for the GBF Fund and the GEF ». IDDRI Note, juillet 2023.

[6] Deutz et al. 2020. Financing Nature: Closing the global biodiversity financing gap. The Paulson Institute, The Nature Conservancy, and the Cornell Atkinson Center for Sustainability. https://www.paulsoninstitute.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/09/FINANCING-NATURE_Full-Report_Final-Version_091520.pdf.

[7] 2030 Targets. The Kunming-Montreal Global Biodiversity Framework. Convention on Biological Diversity. https://www.cbd.int/gbf/targets

[8] The Coalition of Finance Ministers for Climate Action. Nature Investments Workshop. November 2023. https://www.financeministersforclimate.org/sites/cape/files/inline-files/Nature%20Investment%20Workshop.pdf

[9] I Care is actively contributing to working groups on this subject and will share a dedicated publication in the coming months.

[10] It received broad support, particularly from the Asia Investor Group on Climate Change (AIGCC, 2022). For more information, please find their detailed feedback here.

[11] There are also joint initiatives such as Act4Nature and the Finance for Biodiversity pledge.

[12] Bourget, B. The various causes of the agricultural crisis in Europe. Fondation Robert Schuman. Feb 2024. https://www.robert-schuman.eu/en/european-issues/738-the-various-causes-of-the-agricultural-crisis-in-europe

Further questions or interest in COP16 for BIODIVERSITY?

>> Contact us <<

Or contact directly Clément Surun, Constance Gires or Guillaume Neveux.