The COP28, opening on November 30th, 2023, in Dubai (United Arab Emirates), aims to assess global climate action for the first time since the Paris Agreement and to achieve strong commitments. Already laden with significance, three themes are on the agenda for the conference:

- Assessing global climate action since the Paris Agreement;

- Supporting mitigation solutions;

- Implementing adaptation measures and ensuring more equitable access to financing.

As the UN warns of a global 2% reduction in greenhouse gas emissions by 2030 instead of the required 43% to meet the Paris Agreement [1], what can we really expect from this new COP28?

A History of COPs with Mixed Results in the Face of Climate Urgency

A flagship event in the climate agenda, the COPs (Conference of Parties), established in 1992, aim to review the implementation of the international convention and set new goals to combat climate change. Each COP involves new commitments, usually ambitious but not legally binding for stakeholders, while the climate crisis continues to intensify. In recent years, COPs have been referred to as “last-chance COPs” in the hope of reaching agreements to address the climate crisis permanently.

For example, the COP26 held in 2021 in Glasgow was the most significant conference since the adoption of the Paris Agreement in December 2015. It was supposed to reach a consensus on crucial points for the effective implementation of the Paris Agreement, such as coal phase-out (which was not adopted by major coal-producing nations like the United States, China, India, and Australia) and increasing the emission reduction ambitions of states. Despite lengthy negotiations, the COP26 did not achieve the desired objectives. Similarly, the COP27 in 2022 in Egypt secured funding for damages suffered by vulnerable countries affected by climate disasters but lacked commitments on reducing reliance on fossil fuels or raising climate ambitions to meet the challenges.

These last two COPs were relatively disappointing in terms of commitments to combat the climate crisis, while the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) released its sixth assessment report, emphasizing the urgency of the situation with increasing greenhouse gas emissions and escalating risks associated with climate change [2].

A First Global Climate Assessment Reveals an Unchanging Reality: The Goals Are Not Met, and the Window of Opportunity Is Closing

During the Paris Agreement, a process of “Global Stocktake” was established to assess the global response to the climate crisis every five years, starting in 2023. The first stocktake aims to evaluate overall progress in reducing greenhouse gas emissions, enhancing resilience to climate effects, and obtaining financing to address the climate crisis. The 17 technical conclusions published in September 2023 in a synthesis report called “Global Stocktake” [3] demonstrate that the goals are far from being achieved and highlight that the window of opportunity is closing.

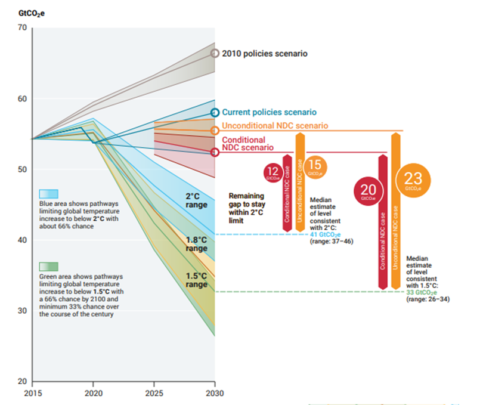

Although some progress has been made since the Paris Agreement (global temperatures are expected to rise by 2.4 to 2.6 °C by the end of the century, compared to a projected 3.7 to 4.8 °C in 2010 [4]), the report clearly emphasizes that greater ambition and urgency are needed on all fronts to combat the climate crisis. It underscores the persistence of an “emissions gap,” noting that current climate commitments do not align with the trajectories necessary to limit global warming well below 2°C or even 1.5°C. This report confirms the findings of the previous “Emissions Gap Report” published by UNEP in 2022, stating that current policies and commitments are far from the Paris Agreement goals to curb climate drift, as shown in the following figure.

Greenhouse Gas Emissions According to Different Scenarios and Emission Gap in 2030 (Median Estimate and Range from Tenth to Ninetieth Percentile), Source: UNEP, Emissions Gap Report 2022

The preparatory report for the global climate action stocktake also outlines a path forward, emphasizing the urgent need for global and systemic transformation and cooperation to reduce greenhouse gas emissions and secure a climate-adapted future. Individuals are placed at the heart of these transitions, with an imperative for resilience and equity in all transformation efforts.

Despite unequivocal messages, this report remains relatively general and provides little new information. It offers a broad “assessment” of the situation with few quantitative details on actions to reduce or limit the consequences of the climate crisis. It acts more as a guiding framework for what the final outcome at COP28 might be without taking a clear position. For example, the report does not specify any dates, roadmaps, or action mechanisms regarding mitigation, adaptation, or financing measures. It remains less binding for the states and stakeholders present, potentially signaling a lack of concrete action or commitment at COP28, even as crucial issues such as mitigation measures have already been placed on the agenda.

Strengthening Mitigation Solutions and Planning Fossil Fuel Phase-out: a Credible Goal for COP28?

During COP28, some of the most significant negotiations will focus on mitigation and low-carbon transition issues. A highlight mentioned in the “Global Stocktake” report of the UNFCCC (Key Result 6) is the need to intensify the development and use of renewable energies and gradually eliminate all fossil fuels for a better energy transition. However, the report acknowledges that fossil fuels will continue to play a significant role for some sectors or communities for a yet-to-be-defined period.

Fossil fuels continue to undergo massive extraction and development

While the Paris Agreement set a crucial global climate goal, many governments and stakeholders have continued to approve and finance new projects related to coal, oil, and gas. The full combustion of current fossil fuel reserves worldwide would result in seven times more emissions than what is compatible with keeping warming well below 2°C.

The rise of fossil fuels is the root cause of the climate crisis, and despite widespread awareness and constant warnings from the scientific community, there is currently no mechanism, treaty, or binding agreement to limit the production of oil, gas, and coal. For example, the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) and the Paris Agreement do not restrict production. Thus, while commitments by states to reduce fossil fuel consumption are essential, they need to be accompanied by commitments to reduce fossil fuel production. An additional agreement may be necessary, even indispensable, to meet the goals of the Paris Agreement.

Planning the “phase-out” of fossil fuels is now necessary

In addition to never mentioning the terms “fossil fuels” or “oil, gas, and coal,” the UNFCCC and the Paris Agreement do not specify any binding deadline for phasing out fossil fuels. Similarly, during the G7 summit in April 2023 in Japan, dedicated to climate issues, energy, climate, and environment ministers from the participating countries (United States, Japan, Germany, France, the United Kingdom, Italy, and Canada) failed to agree on a fossil fuel phase-out date. The ministers pledged to “accelerate” their “phase-out” of fossil fuels in all sectors but without setting a new deadline [5]. They vaguely incorporated this goal into their efforts to achieve carbon neutrality by 2050 “at the latest.”

The inability to agree on a fossil fuel phase-out date demonstrates a lack of seriousness and ambition today, despite the increasing climate-related events (floods, wildfires, etc.) and their growing severity. Concrete formalization of a transition plan with a fossil fuel phase-out date towards other low-carbon energy sources is essential to honor the Paris Agreement.

Other mitigation measures will not be sufficient to limit climate warming

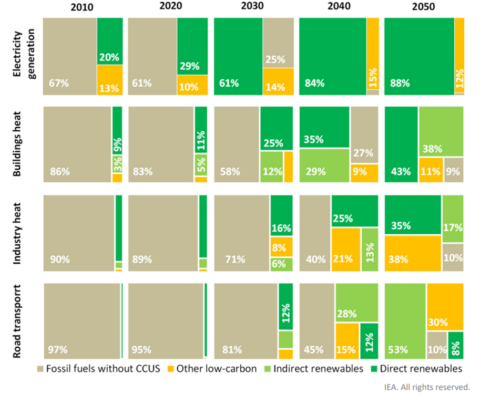

In May 2023, the President of COP 28, Sultan Ahmed al-Jaber, present at the Climate Petersberg Dialogue in Berlin, called to “triple” global renewable energy production capacity by 2030, to “double hydrogen production,” and to “double energy efficiency improvement” to contribute to limiting climate warming, in line with the conclusions of the “Net Zero by 2050” report [6] from the International Energy Agency (IEA).

Part des combustibles dans la consommation totale d’énergie pour certaines applications, rapport « Net Zero by 2050 » de l’IEA, 2021

However, Sultan Ahmed al-Jaber did not endorse the goal of a fossil fuel phase-out and urged countries to retain “all existing sources of energy.” He relies on carbon capture and storage technologies, not yet deployed on a large scale, to reduce greenhouse gas emissions. These statements seem less credible coming from the CEO of the Abu Dhabi National Oil Company (ADNOC), the national oil company of the United Arab Emirates, which has a score of 3.8/100 in the benchmark [7] conducted by the World Benchmark Alliance using the ACT (Assessing Low-Carbon Transition) methodology. This casts doubt on the reliability and credibility of the President of COP 28 and the host country, the United Arab Emirates. Consequently, many scientists and experts have recently called for a boycott of COP28 in an op-ed [8] published in Le Monde, denouncing its absurdity and danger. They urge states to reinvent the COP model and place it under the auspices of the UN.

If COP28 aims to address the climate urgency, it will be imperative to make concrete, planned, and quantified commitments on mitigation measures, starting with planning the phase-out of fossil fuels, especially coal. However, mitigation alone cannot ensure an effective environmental transition, and it needs to be coupled with increasingly important adaptation solutions due to the inadequacy of collective commitments to reduce greenhouse gas emissions.

Implementing Adaptation Measures: early limits of our adaptive capacity have already been reached, and means are still largely insufficient

Wildfires in Canada, heatwaves and droughts across Europe, hurricanes in Guadeloupe and Mexico—there has been a real acceleration of climate disasters in recent years, even months. These events are no longer rare today, and it is necessary to address them now. While mitigation measures dominate international discussions and treaties, the question of adapting to climate change is becoming increasingly fundamental for organizations and businesses, as highlighted in the latest IPCC report. Despite proven and effective progress in planning and implementing adaptation measures across all sectors and regions, there are still gaps in adaptation, and they continue to widen [9].

The “Global Stocktake” synthesis report, on which discussions will be based, recalls that some limits to adaptive capacity have already been reached in several regions and sectors. In some places, maladaptation effects, such as construction in erosion or marine submersion zones, are observed. In a previous report contributing to the global assessment, scientists highlighted that over 3 billion people would be vulnerable to climate risks in “vulnerability hotspots” by 2050—twice as many as today. However, without action, adaptation measures that are currently feasible and effective will be limited and less effective in the future with increasing global warming. Losses and damages will intensify, and other systems (natural and/or human) will also reach their own adaptation limits, making intervention difficult.

The “Global Stocktake” report also emphasizes the urgent need to increase technical and financial support for adaptation and address losses and damages, especially for vulnerable communities. Current global financial flows for adaptation are still largely insufficient to implement various necessary adaptation measures, especially in developing countries. International climate finance dedicated to adaptation (between 4 and 30% of climate finance flows, depending on sources) has increased but remains inadequate, constraining adaptation efforts [10]. It is essential to note that the goal of developed countries to jointly mobilize $100 billion per year by 2020 has not yet been achieved [11].

Recommendations for reviewing and adopting measures to operationalize the new fund for losses and damages and funding modalities have already been shared with parties and will be on the COP 28 agenda. Negotiations will also focus on providing adequate and predictable financial support to developing countries for climate action, including the establishment of a new collective quantified climate finance target in 2024. The UN Climate Finance Standing Committee has been invited to prepare a report on doubling adaptation financing for review at COP28 [12]. It should be noted that financial commitments may also cover existing COP funds, such as the Fund for the Least Developed Countries, the Special Climate Change Fund, or the Green Climate Fund.

Parties have finally agreed on the need to establish a global adaptation goal [13] at the upcoming COP, as decided during the Bonn Conference in June 2023, a preparatory event for COP28. Overall, optimizing the support provided by existing financing mechanisms, including considerations of coherence, complementarity, and coordination, will be a priority for COP28.

Conclusion

In continuation of COP27 and considering the extreme climate events that have marked 2023 worldwide, this new COP in Dubai at the end of November is expected to increase technical and financial support for adaptation. It will also structure financing methods to address escalating losses and damages. While there may be hope for progress in adaptation and its financing, the situation is much less clear on the mitigation front.

Beyond controversies about the relevance of COP28’s presidency by a country and a president with limited credibility in climate action, preparatory work and statements from parties ahead of COP28 suggest that, once again, financial resources for mitigation measures and commitments (including financial ones) to limit fossil fuel production will not be on the negotiation agenda. As “every tenth of a degree counts,” this would further solidify the observed “shift” (noted in recent IPCC reports) of attention from the “mitigation” theme to the detriment of the “adaptation” theme. It would then become legitimate to question whether COP28 should acknowledge, from the outset, the impossibility of meeting the commitments of the Paris Agreement to limit global warming to +1.5°C. The next report could provide new insights into the gap between ‘Paris Agreement’ trajectories and the current trajectory encompassing all state commitments.

Finally, it is interesting to note that business leaders are now calling on states to rethink the COP model and place it under the supervision of the UN. The urgent need for global and systemic transformation and cooperation suggests a more direct participation to overcome a governance and action model that fails to produce results commensurate with the challenges.

Sources:

[1] unfccc.int/sites/default/files/resource/cma2023_12.pdf?mc_cid=6b1f7987e0&mc_eid=835665a2e6

[2] report.ipcc.ch/ar6syr/pdf/IPCC_AR6_SYR_SPM.pdf

[3] Technical dialogue of the first global stocktake. Synthesis report by the co-facilitators on the technical dialogue | UNFCCC

[4] Emissions Gap Report 2022 (unep.org)

[5] G7 : la sortie des combustibles fossiles n’est pas pour tout de suite (courrierinternational.com)

[6] Net Zero by 2050 – A Roadmap for the Global Energy Sector

[7] Oil and Gas Benchmark (worldbenchmarkingalliance.org)

[8] L’appel au boycott de la COP28 de 180 responsables d’entreprises : « Organiser une conférence sur le climat à Dubaï est absurde et dangereux » (lemonde.fr)

[10] 20250_4pages-GIEC-2.pdf (ecologie.gouv.fr)

[11] Mobilizing more financial support for developing countries | UNFCCC

[12] Id. 11

[13] Bonn Climate Conference Closes With Progress on Key Issues, Laying Groundwork for COP28 | UNFCCC

Find all of our latest publications in the Infos tab of our website